The pioneering Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723 – 1790) assumed that we are “rational-economic.” He expected us to use facts and reason to analyze potential outcomes and then make logical choices based upon rational self-interest. If Mr. Smith were alive today, he would likely be surprised about the amount which continues to be invested in high-cost mutual funds with mediocre performance. Low-cost index funds are the more rational choice, since they have a very high probability of better performance than the same strategy implemented through high-cost mutual funds.

2

Advice from the chatbot

Investment through high-cost mutual funds is one of the most prevalent (and easy to correct) shortcomings of the individual investment portfolios we inherit. Even the chatbot ChatGPT appears to agree, advising investors as follows[1]:

It’s generally recommended to diversify your investments across multiple asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities. Additionally, investing in low-cost index funds can provide broad exposure to various markets and can be a good option for long-term growth.

Active equity funds rarely beat passive index funds

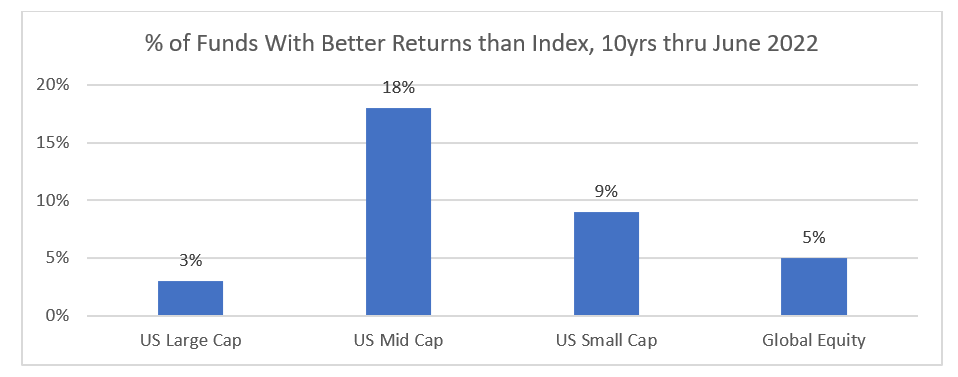

Reports compiled by S&P Dow Jones Indices[2] routinely show that the vast majority of active equity managers fail to outperform their investment benchmarks. For instance, in the ten-year period ended June 2022, 97% of US large-cap equity funds had performance net of fees which was below the S&P 500 index return. Eighty-two percent of mid-cap funds, 91% of small-cap funds and 95% of global equity funds were also behind their respective benchmarks.

The performance shortfalls can be meaningful. For instance, the average US large cap mutual fund performance was 2.4% per year worse than the S&P 500. That 2.4% adds up – after ten years an S&P 500 index investor would have 25% more in their account than the average active mutual fund investor.

It gets even worse. The funds included in the S&P reports are those available in June 2012 which remained in existence in June 2022. Only about 60% of the US large cap funds on offer in 2012 survived to 2022. The ones which did not make it were also likely behind the benchmark at the time they closed. Moreover, investors often “churn” the fund lineup in their portfolios – selling the recent losers and buying the recent winners, which further erodes returns relative to just buying an index fund and sticking with it.

Given this information, one might expect a rational-economic person to favor low-cost index funds, but that is not the case. Assets in low-cost index funds are growing rapidly, but at $11 trillion they remain a smaller portion of the $126 trillion asset management industry than active funds.

Why does this irrationality persist?

Most people do not realize that there are two types of participants who provide investment management services to individuals, some of whom are fiduciaries and the rest who are not. Registered Investment Advisors (RIAs) are required to be fiduciaries. As fiduciaries, RIAs are legally required to put the client’s interest ahead of the advisor’s interest, avoid conflicts of interest (or disclose any if they arise) and offer complete and accurate investment advice.

Many individuals trust their money to broker-dealers, insurance companies and private bankers who are NOT fiduciaries. These organizations are bound by a much looser “suitability” standard. The suitability standard merely requires that the advisor believe the investment choice is “suitable” for the clients. Crucially, “suitability” does not require that the choice recommended to the client is in the client’s best interest.

An example of an investment which might be rejected by a fiduciary, let’s look at American Funds Growth Fund of America (AGTHX), which invests in US growth stocks. According to Bloomberg, in the ten years through February 7, 2023, an investor in AGTHX gained 12.29% per year. The S&P 500 growth index was up 13.89% per year in the same period. As an alternative to AGTHX, the low-cost Vanguard Growth ETF (VUG) earned 13.74% per year, nearly all the index return. Yet AGTHX has $215 billion in assets, while VUG has $79 billion.

What accounts for the large investment in AGTHX? The main reason, we believe, is that advisors who operate under a “suitability” standard receive payments from American Funds when they choose AGTHX, while they would not receive payments from Vanguard for selecting VUG. AGTHX charges the investor an expense ratio of 0.61% of assets. Of that 0.61%, 0.24% is a “12b1” fee, the amount of the fee which the fund manager can pay over to the advisor as an incentive to put their client in the fund. Moreover, AGTHX has a Front Load of 5.75%, a Back Load of 1.0% and an Early Withdrawal Fee of 1.0%, additional ways to use the client’s money to provide an incentive for the advisor to choose AGTHX over lower cost funds. Meanwhile, Vanguard charges investors in VUG just 0.04% per year.

This illustration helps us understand why these mutual funds continue to prosper. An individual who fully understands their rational self-interest would likely favor VUG over AGTHX. Yet, AGTHX can be the rational choice for the insurance company or broker-dealer because it is much more rewarding to themselves than VUG would be. There’s a clear conflict between the best interest of the broker and the best interest of the client. The client puts misguided trust in the broker and ends up in a high-cost poor-performing fund as a result.

David Swenson managed the Yale University endowment for decades, achieving preeminent investment outcomes. In 2005 he wrote a guidebook for individual investors called “Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment.” Much of the book is a scathing critique of the mutual fund industry and its enablers. The book praises Vanguard and strongly recommends investment through low-cost index funds.

Where are the regulators?

It is not in the client’s best interest to pay a 5.75% front load and 0.62% annual fees for a large cap US equity fund with mediocre performance. Who is looking out for the clients?

In 2015, a major overhaul was proposed by the US Department of Labor which would broadly expand the fiduciary rule to cover all organizations which advise on retirement savings. This rule change was fiercely opposed by the financial services industry, which stood to lose billions of dollars of fee income, “load” revenue and 12b-1 fees. The industry opposition has largely been successful, with a series of judicial and legislative setbacks preventing the fiduciary rule from taking effect so far. Some states have adopted their own fiduciary rules to protect investors, and some financial institutions have voluntarily adopted a fiduciary standard even though not yet required by law.

Here we have politicians acting in their rational self-interest. No industry makes more US political contributions than the financial services industry. A politician is likely to obtain more campaign contributions going along with the industry than opposing it. Moreover, it is not likely that enough voters understand the difference between a “suitability” standard and a “fiduciary” standard to affect the outcome of an election.

But there are some good active fund managers, right?

An organization which can identify the most capable managers in advance has a rational basis to entrust money to them. Under David Swenson, the Yale endowment office was among the best in the world at doing just that.

As an individual investor, it is important to recognize that the way that you would select a fund manager, or the way that the organization advising you selects managers, is not remotely close to the capability that the Yale endowment office applies to selecting its managers. Another recurring theme of the Swenson book is “don’t try this at home,” you cannot do what Yale does.

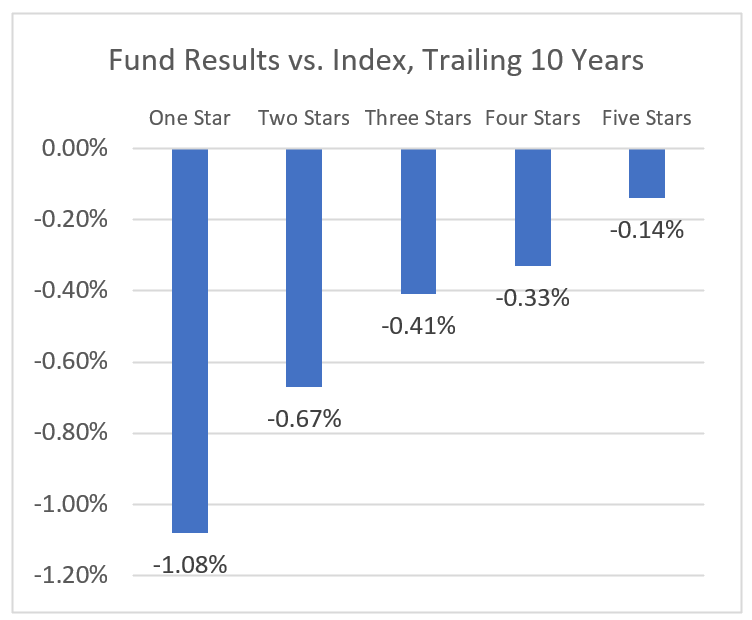

Many individuals rely on simple fund rankings, such as the Morningstar “star” system to choose funds. According to Morningstar, the rankings are slightly predictive – funds which received five stars in June 2012 had ten-year annual performance about 1% better than the one-star funds[3].

Morningstar also calculates the performance vs. index for each star cohort. As the chart indicates every rating category had ten-year performance behind its benchmark index. Low-cost index funds would have had better results than even the five-star funds.

Morningstar even once published a study which admitted that selecting funds with the lowest expense ratios led to better outcomes than selecting the five-star funds. Dimensional Fund Advisors has published similar research about the impact of fees on outcomes.[4] According to Dimensional, only 6% of the funds in the highest quartile of expense ratio were ahead of their index benchmarks over 20 years, while 31% of the funds in the lowest expense quartile beat their benchmarks.

Summary

We heartily agree with ChatGPT and David Swenson – the rational-economic choice is to implement investment portfolios at the lowest implementation cost, which usually means a low-cost index fund. We believe that incentive payments from mutual fund companies to advisors who operate under a “suitability” standard are a key reason that high-cost active mutual funds continue to have a large (albeit declining) share of investors’ money. It is important for individuals to understand whether they are receiving investment advice from a fiduciary. If your advisor is not a fiduciary, we suggest you look up the expense ratios of the funds in your portfolio and ask your advisor:

- How does the net-of-fee performance of my funds compare to the performance of the lowest cost index fund in each category?

- How much of the expense ratio of the fund goes to you?

[1] https://chat.openai.com/chat

[2] Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/research-insights/spiva/

[3] Source Morningstar: https://www.morningstar.com/articles/1097971/rating-morningstars-fund-ratings

[4] Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors, Fund Landscape 2022