The familiar stock market adage “Sell in May and go away” has its origins in 18th century England, yet we seem to hear it repeated every year. Since it’s May again and the outlook is as murky as ever, it would be tempting to park money somewhere safe and just enjoy the summer. We thought it would be a fun exercise to test if the “Sell in May” strategy has any merit. As it turns out:

- In the last 50 years, “Sell in May” would usually have been good advice

- However, there is not a sound fundamental basis for this

- There is a stronger case to “Sell in May” this year

Origins of “Sell in May”

In 18th century England, the investing elite of London would reduce equity holdings in May and literally “go away” to second homes in the countryside. The full expression was: “Sell and May and go away, come back on St Leger’s Day.” The St Leger Stakes is the oldest of Britain’s five Classic horse races, taking place in September or October each year. The “Sell in May” advice is also referred to as the “Halloween indicator” due to the tendency of stock market returns to improve after Halloween.

Results of the “Sell in May” Strategy

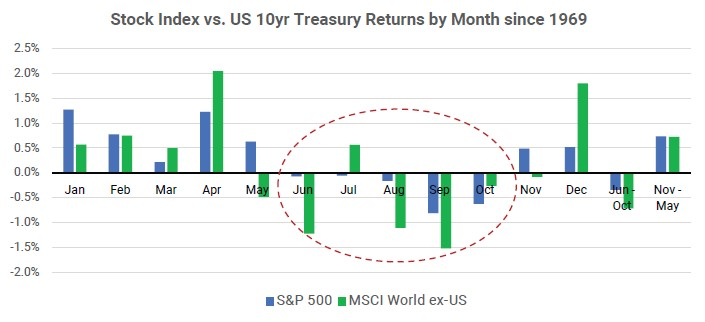

The chart below compares the return of the US and international stock indices to the return of the US ten-year treasury note, by month. There has been a clear seasonal pattern. The US and international indices have had a worse return than bonds in June through October, and a better return otherwise.

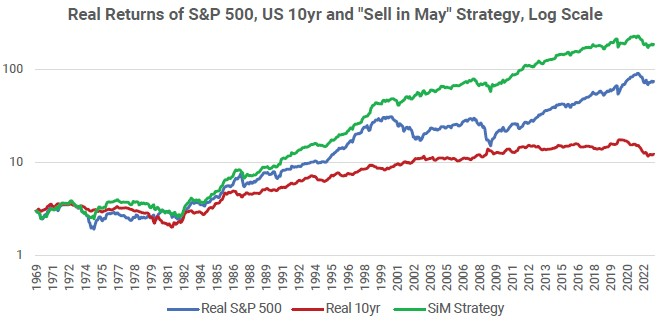

From December 1969 to the present, an investor who owned the S&P 500 in November through May and US ten-year treasury notes in June through October would have enjoyed a 2% per year higher real return than an investor who owned the S&P 500 the whole time. The “Sell in May” strategy also had a lower risk of loss, since the investor was in fixed income investments five months of the year.

How could a simple strategy like this have worked so well?

“Sell in May” violates fundamental principles of equity investing. Investors are advised to always stay in the stock market, since one never knows when the best returns will come. But in fact, it would have been better to be in bonds instead of stocks five months of each year. Investors are also advised that markets are “efficient” and therefore no investment strategy which relies on information which is commonly known is likely to be successful. But it looks like information which everyone knows – it’s May again – would have been the foundation of a profitable strategy.

There is no obvious reason why a simple strategy like “Sell in May” should work, but here are some potential explanations for this anomaly:

- Consumer spending by month tends to be higher in November to May, given the impact of holiday gatherings, winter gifts and year-end bonuses

- Active investors lower their stock market risk during summer vacations

- Trading volumes are lower in the summer and the less volatile stocks outperform

- Risk appetite surges in January and then recedes during the year

- Traders take more risk and high-volatility stocks outperform when the year begins

Caveat: The impact of recessions?

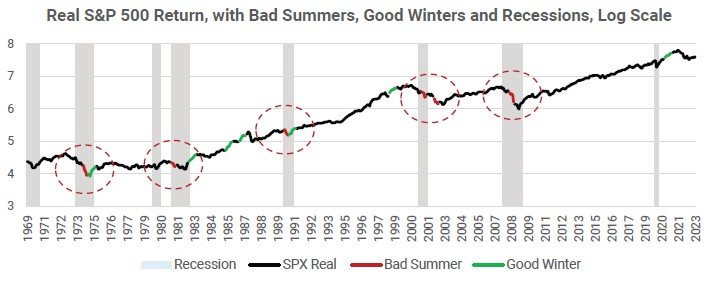

The 50-year averages for summer and winter stock market returns are heavily influenced by a small number of very bad summers and very good winters. Probably the most important reason why “Sell in May” would have worked in recent decades is the timing of the recessions. The six worst summers are the red sections of the line below; five of the six occurred in the early months of a US recession. In contrast, four of the eight best winters (in green) were during the recovery from a US recession.

A common argument for staying invested all the time is that if you miss even a small number of the best performing days in the market, you end up much worse off. What’s less discussed is the flip side of the same argument – if you miss the very worst days you can be much better off. This “Sell in May” phenomenon could be simply a coincidence of the recent recession timing.

What about May 2023?

“Going away” is unlikely to work every May. However, it’s more tempting this year as there are two major issues that concern us: 1) corporate profits; 2) the recent banking crisis finally tipping the US economy into a recession.

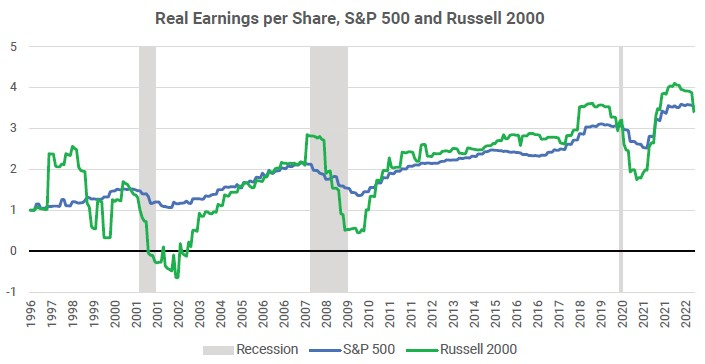

First on corporate profit. The current market expectation is that earnings for the S&P 500 will be about the same in 2023 as in 2022.

We are not so sure. The earnings of small capitalization companies tend to be a leading indicator. Earnings of the Russell 2000 index of smaller US stocks are already 17% lower than last year’s peak, a sign that earnings of large companies may follow suit. Typically, real earnings of the S&P 500 fall about 20% in a recession, which would be a much worse outcome than current expectations. Price/earnings ratios usually fall in recessions as well, which would be an additional negative impact on stock prices.

The second main concern is the impact of the current stress on banks. The economic cycle is often referred to as the “credit cycle” because of the importance of lending to economic activity. When the interest rate demanded on loans rises and the availability of loans falls, there is a negative impact on economic activity. The recent string of bank failures and continued deposit outflow have added severe pressure on bank lending now, which could tip the US economy into a recession in the next few quarters. On balance, we would argue that the probability of a recession is higher now than it was at the beginning of the year. This has also caused the yield curve to be less inverted, which means that bond market investors expect the economy is getting closer to a recession. (When the economy is in recession, the yield curve would begin to steepen in reflection of Fed cutting interest rates.)

Summary

While “Sell in May and go away” would have been a worthwhile strategy over the past fifty years, we do not recommend it as a general rule as there is not a compelling enough fundamental case for the strategy. We think there is a strong possibility that it simply is a coincidence that recent recessions had their most severe impact on stock prices in the summer.

Specifically for May 2023, we continue to be cautious in our risk outlook. The strong equity performance year to date does not seem to reflect the rising recession risk in the US economy, even after several rather large-scale bank failures, and certainly does not price in the possibility of lower corporate profitability. We remain underweight in risk assets at current valuation levels.