Much has been written and discussed over the weekend regarding the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and the potential spillover impact to the overall banking system. Now that federal regulators have stepped in, should we expect everything to return to business as usual?

We think the answer is no. While the backstopping of bank deposits indeed can stop an imminent bank run, the unwinding and deleveraging process across the financial system has probably just begun. We would advise our clients to use this opportunity to reassess your financial arrangements in the near term, particularly your level of bank deposits, and prepare your investment portfolio for the deleveraging to come.

What goes up must come down, eventually

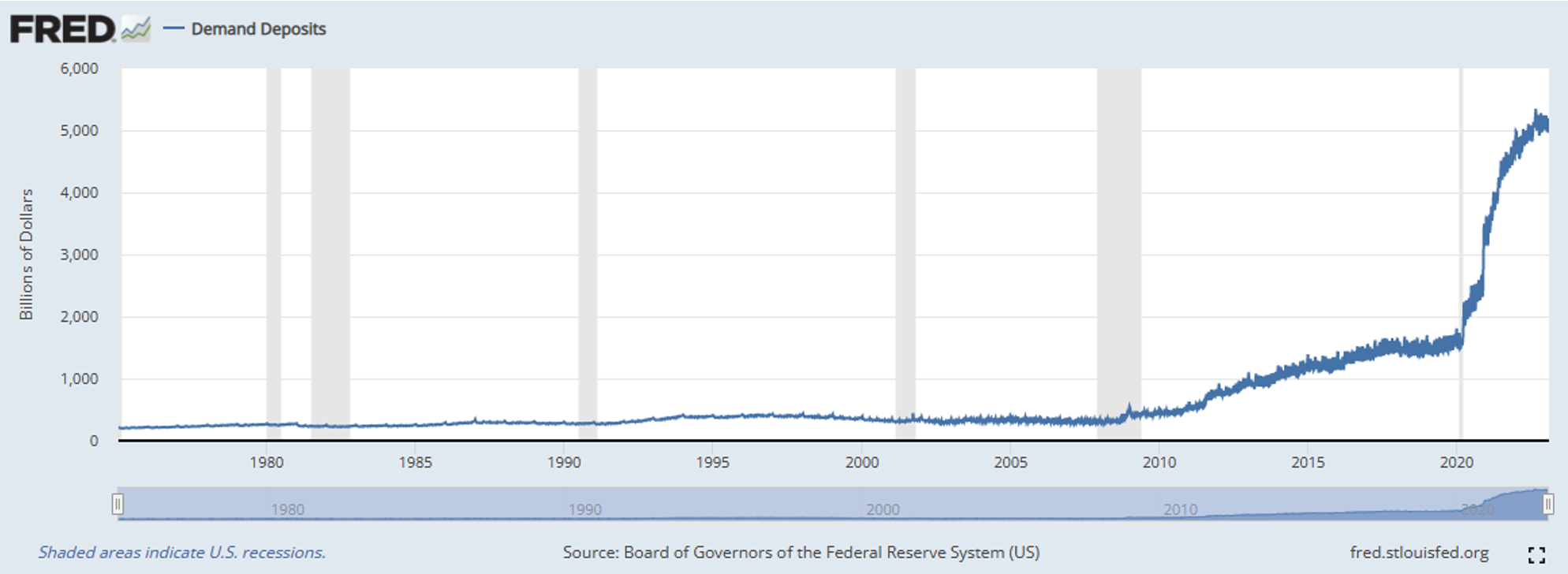

Deposits have surged across the banking system in the last three years. As this chart from the Federal Reserve shows, demand deposits in the US more than tripled from the beginning of 2020 to today, from about $1.5 trillion to $5 trillion.

The massive escalation in deposits was kicked off by the pandemic stimulus efforts, both in terms of monetary policy (the Fed’s unprecedented quantitative easing) AND the fiscal policies (the governments’ stimulus packages to individuals and small businesses). Additionally, cheap and easy borrowing combined with an uncertain future prompted decision-makers along the whole spectrum from individuals, start-ups to giant global corporations to raise precautionary funds and hoard cash.

The Silicon Valley Bank failure

Deposits at Silicon Valley Bank also more than tripled, consistent with the national trend, with a further boost from the frenetic equity and debt raising among tech startups. SVB ended the first quarter of 2020 with just over $60 billion in total deposits and had nearly $200 billion by the end of the first quarter of 2022. Usually, a jump in deposits is a blessing for a bank, which can earn a huge spread between what it earns on the money and what it pays depositors. However, the surge in deposits at SVB turned into a curse, due to colossally bad financial risk management. As has been reported, SVB invested most of its new deposit money, about $100 billion, in longer-term U.S. Treasurys and government-backed mortgage securities. Those investments were “safe” in the sense that they are US government obligations and SVB would be repaid. But, as SVB investors discovered to their dismay, they were not “safe” in the sense that they were protected from loss.

Once SVB had bought its $100 billion in Treasury and mortgage securities, it should have known that any rise in long-term US interest rates of 2% or more could be fatal – creating enough losses to wipe out all the bank’s capital. The fact that the bank was flirting with disaster should have been discussed and dealt with by senior management and the board.

When indeed interest rates rose enough to cause SVB to be technically insolvent, it seems that few noticed at first. At the beginning of March 2023, just days before bankruptcy, SVB shares outstanding were worth $17 billion. SVB had a strong A3 bond rating from Moody’s and a slightly weaker investment grade ranking of BBB from Standard & Poor’s. Now the SVB shares are probably worthless, and the bonds are trading at less than half of face value.

What about First Republic?

Another bank in the San Francisco area which clearly could have done a better job of financial risk management is First Republic Bank. First Republic was frequently mentioned in the “who’s next” commentary surrounding the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Like SVB, it has unrealized losses on its assets which have caused the market value of its liabilities to become larger than the market value of its assets. As at SVB, First Republic’s asset values were hit hard by the rise in US interest rates. A difference is that at First Republic the losses are primarily from declines in the value of long-term mortgages rather than the value of long-term government securities.

It should have been well known within First Republic that it was possible, even likely, that rising interest rates would cause the net market value of the bank to become negative. This negative net worth does not mean that First Republic will fail, especially now that regulators have created a general backstop for depositors. If there is no run on the bank, First Republic will not be forced to realize the losses on its mortgage assets, in the way SVB was forced to realize the losses on its Treasury holdings.

A major advantage First Republic has which should help it get out of trouble is that it pays so little to its depositors. It has $75 billion in noninterest-bearing checking deposits and another $93 billion in deposits on which it pays an average of only 0.71%. The difference between what First Republic pays on these deposits and what its customers could otherwise earn if they moved their money to Treasury bills is about $8 billion a year. Clearly, First Republic needs those profits today, but if you are one of the depositors you could capture that value for yourself instead of leaving it for them.

The coming exodus from banks

If people behave rationally, what ought to happen is a decline in the amount of bank deposits in the system. And indeed, the dynamics which led to skyrocketing deposits are reversing. The COVID-era stimulus payments are over, and beneficiaries of the stimulus are now drawing on their savings. Instead of quantitative easing, the Fed is engaged in quantitative tightening, removing assets from the banking system. With the rise in interest rates, it is much less sensible for companies to borrow “rainy day” money and stash it in a low-yield bank deposit. And anyone with a large bank deposit is leaving a lot of money on the table, since so much more interest can be earned in Treasury bills. As a consequence of these factors, we believe the unprecedented surge in bank deposits is about to transition to an unprecedented shrinking.

Summary

1) We believe the challenges faced by Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic are due to poor risk management at those banks rather than being a sign of systematic stress across the banking system.

2) Don’t hold cash. While particularly true in times of distress, even when things are “normal”, do not hold cash. There is rarely a ‘free lunch’ in financial markets but buying treasury securities instead of holding cash not only provides security but also enhances yield. And yes, even for amounts below FDIC insured amounts.

Treasury holdings are segregated from bank holdings – unlike cash – so outside of outright fraud (e.g., FTX where there was a comingling of funds) even with a bank failure your treasury holdings will be protected.

It is very hard for individuals to know whether their bank is badly managed. Even the professional investors in the stock market and the expert analysts at the credit rating agencies missed the signs of trouble at Silicon Valley Bank. This uncertainty about bank health should provide an additional incentive to limit one’s exposure to uninsured deposits at banks.

Atlas continues to advocate for independent and objective investment advice. Over the years we have been troubled by wealth management units at banks offering advice that is clearly tainted by the mixed motivations of the bank. Be it fancy and opaque investment products that benefit the bank or simply the advice to maintain a “healthy” checking balance in exchange for an attractively priced loan – keep your investment advice with as few conflicts of interests as possible.

Much has been written and discussed over the weekend regarding the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and the potential spillover impact to the overall banking system. Now that federal regulators have stepped in, should we expect everything to return to business as usual?

We think the answer is no. While the backstopping of bank deposits indeed can stop an imminent bank run, the unwinding and deleveraging process across the financial system has probably just begun. We would advise our clients to use this opportunity to reassess your financial arrangements in the near term, particularly your level of bank deposits, and prepare your investment portfolio for the deleveraging to come.

What goes up must come down, eventually

Deposits have surged across the banking system in the last three years. As this chart from the Federal Reserve shows, demand deposits in the US more than tripled from the beginning of 2020 to today, from about $1.5 trillion to $5 trillion.

The massive escalation in deposits was kicked off by the pandemic stimulus efforts, both in terms of monetary policy (the Fed’s unprecedented quantitative easing) AND the fiscal policies (the governments’ stimulus packages to individuals and small businesses). Additionally, cheap and easy borrowing combined with an uncertain future prompted decision-makers along the whole spectrum from individuals, start-ups to giant global corporations to raise precautionary funds and hoard cash.

The Silicon Valley Bank failure

Deposits at Silicon Valley Bank also more than tripled, consistent with the national trend, with a further boost from the frenetic equity and debt raising among tech startups. SVB ended the first quarter of 2020 with just over $60 billion in total deposits and had nearly $200 billion by the end of the first quarter of 2022. Usually, a jump in deposits is a blessing for a bank, which can earn a huge spread between what it earns on the money and what it pays depositors. However, the surge in deposits at SVB turned into a curse, due to colossally bad financial risk management. As has been reported, SVB invested most of its new deposit money, about $100 billion, in longer-term U.S. Treasurys and government-backed mortgage securities. Those investments were “safe” in the sense that they are US government obligations and SVB would be repaid. But, as SVB investors discovered to their dismay, they were not “safe” in the sense that they were protected from loss.

Once SVB had bought its $100 billion in Treasury and mortgage securities, it should have known that any rise in long-term US interest rates of 2% or more could be fatal – creating enough losses to wipe out all the bank’s capital. The fact that the bank was flirting with disaster should have been discussed and dealt with by senior management and the board.

When indeed interest rates rose enough to cause SVB to be technically insolvent, it seems that few noticed at first. At the beginning of March 2023, just days before bankruptcy, SVB shares outstanding were worth $17 billion. SVB had a strong A3 bond rating from Moody’s and a slightly weaker investment grade ranking of BBB from Standard & Poor’s. Now the SVB shares are probably worthless, and the bonds are trading at less than half of face value.

What about First Republic?

Another bank in the San Francisco area which clearly could have done a better job of financial risk management is First Republic Bank. First Republic was frequently mentioned in the “who’s next” commentary surrounding the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Like SVB, it has unrealized losses on its assets which have caused the market value of its liabilities to become larger than the market value of its assets. As at SVB, First Republic’s asset values were hit hard by the rise in US interest rates. A difference is that at First Republic the losses are primarily from declines in the value of long-term mortgages rather than the value of long-term government securities.

It should have been well known within First Republic that it was possible, even likely, that rising interest rates would cause the net market value of the bank to become negative. This negative net worth does not mean that First Republic will fail, especially now that regulators have created a general backstop for depositors. If there is no run on the bank, First Republic will not be forced to realize the losses on its mortgage assets, in the way SVB was forced to realize the losses on its Treasury holdings.

A major advantage First Republic has which should help it get out of trouble is that it pays so little to its depositors. It has $75 billion in noninterest-bearing checking deposits and another $93 billion in deposits on which it pays an average of only 0.71%. The difference between what First Republic pays on these deposits and what its customers could otherwise earn if they moved their money to Treasury bills is about $8 billion a year. Clearly, First Republic needs those profits today, but if you are one of the depositors you could capture that value for yourself instead of leaving it for them.

The coming exodus from banks

If people behave rationally, what ought to happen is a decline in the amount of bank deposits in the system. And indeed, the dynamics which led to skyrocketing deposits are reversing. The COVID-era stimulus payments are over, and beneficiaries of the stimulus are now drawing on their savings. Instead of quantitative easing, the Fed is engaged in quantitative tightening, removing assets from the banking system. With the rise in interest rates, it is much less sensible for companies to borrow “rainy day” money and stash it in a low-yield bank deposit. And anyone with a large bank deposit is leaving a lot of money on the table, since so much more interest can be earned in Treasury bills. As a consequence of these factors, we believe the unprecedented surge in bank deposits is about to transition to an unprecedented shrinking.

Summary

1) We believe the challenges faced by Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic are due to poor risk management at those banks rather than being a sign of systematic stress across the banking system.

2) Don’t hold cash. While particularly true in times of distress, even when things are “normal”, do not hold cash. There is rarely a ‘free lunch’ in financial markets but buying treasury securities instead of holding cash not only provides security but also enhances yield. And yes, even for amounts below FDIC insured amounts.

Treasury holdings are segregated from bank holdings – unlike cash – so outside of outright fraud (e.g., FTX where there was a comingling of funds) even with a bank failure your treasury holdings will be protected.

It is very hard for individuals to know whether their bank is badly managed. Even the professional investors in the stock market and the expert analysts at the credit rating agencies missed the signs of trouble at Silicon Valley Bank. This uncertainty about bank health should provide an additional incentive to limit one’s exposure to uninsured deposits at banks.

Atlas continues to advocate for independent and objective investment advice. Over the years we have been troubled by wealth management units at banks offering advice that is clearly tainted by the mixed motivations of the bank. Be it fancy and opaque investment products that benefit the bank or simply the advice to maintain a “healthy” checking balance in exchange for an attractively priced loan – keep your investment advice with as few conflicts of interests as possible.

Share to Social Media!

Subscribe To Receive The Latest News

Related Posts

June 2024 Recap

May 2024 Recap

April 2024 Recap

March 2024 Recap