What’s Discussed

Many of you who read our papers would qualify to invest in hedge funds. However, if your hedge fund portfolio resembles the average of the hedge fund universe, it is better to not invest in hedge funds at all. The reasons for individual investors to steer clear of hedge funds include:

- Not diversifying – hedge funds repackage investment risks you already have

- Vanished skill-based return – better to obtain similar investment exposure in a low cost way

- Not “absolute return” – will experience losses, often at the worst times

- Enormous fees – lucrative for the hedge fund manager but not for you

- Not transparent – delayed and partial information about your holdings

- Not liquid – takes a long time to get your money back

- Very tax inefficient – large and unpredictable obligations for taxable investors

What is a Hedge Fund?

The term “hedge fund” covers dozens of types of investment strategies, with many subtypes within types. One common factor is an emphasis on active security selection – exploiting investment “mistakes” made by other participants in the markets.

Another common element to hedge funds is the regulatory structure. If a fund limits the number of its investors and all investors are “qualified” (affluent and presumably sophisticated) the fund manager is exempt from the regulations of the Investment Company Act of 1940 and its subsequent amendments and rules (often referred to as the “40 Act”). The 40 Act protects investors by requiring fund managers to regularly disclose information about their business, strategies, and investment holdings. Because hedge funds are exempt from the 40 Act, hedge fund investors have fewer protections.

The witty head of AQR, a very successful hedge fund, once described the category as follows (Cliff Asness, 2004): “Hedge funds are investment pools that are relatively unconstrained in what they do. They are relatively unregulated (for now), charge very high fees, will not necessarily give you your money back when you want it, and will generally not tell you what they do. They are supposed to make money all the time, and when they fail at this, their investors redeem and go to someone else who has recently been making money. Every three or four years they deliver a one-in-a-hundred year flood.”

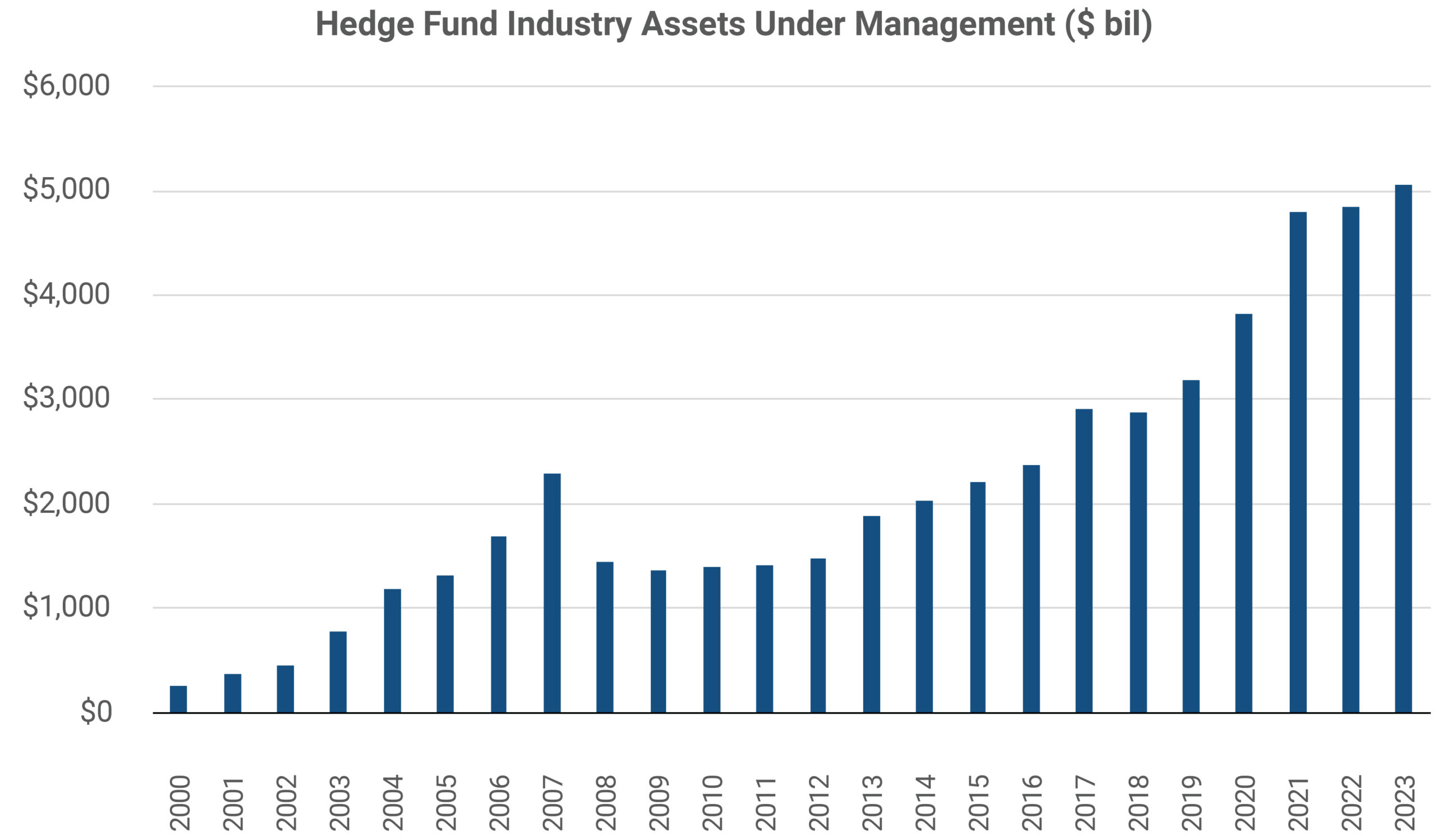

Despite the lack of investor protections and other drawbacks, hedge funds continue to attract investor capital. Assets under management have grown steadily since the Global Financial Crisis, reaching $5 trillion by the end of 2023[1].

Not Diversifying

Hedge funds are marketed as the ideal diversifying investment, a source of consistently positive investment outcomes which are not correlated to the equity market. The reality is that hedge funds, as a group, are an inefficient and expensive way to obtain more equity market exposure. Since 2010, the correlation of the monthly returns of the hedge fund index[2] and the S&P 500 has been 0.75. Hedge funds are closer to perfectly correlated with equities (1.0 correlation) than uncorrelated (0.0). That high correlation to equities might still be acceptable if the returns were high enough, but…

No Net Skill-Based Return

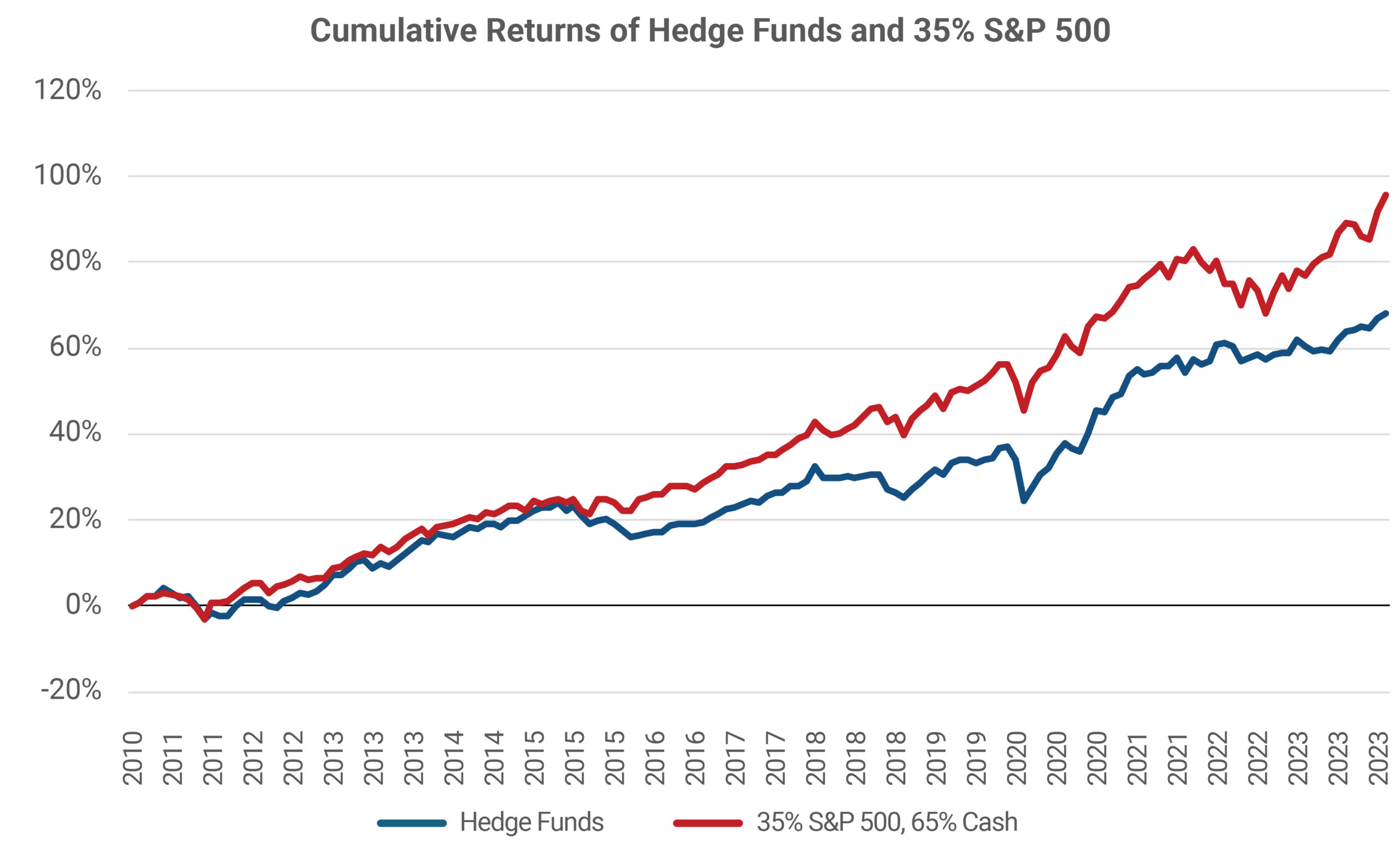

Since 2010, one could have replicated the performance of the hedge fund industry as a group at the same level of investment risk with a portfolio holding 35% in the S&P 500 index and 65% in three-month US Treasury bills. The following chart[3] compares the cumulative returns of the two investment strategies. The pattern of the lines is similar. A strategy with 35% in the S&P 500 and 65% in cash would have returned 5.5% per year, while the hedge fund universe delivered only 4.1% per year. The hedge fund index is biased upward[4], so the real hedge fund return was most likely even worse than 4.1% per year. In retrospect, hedge funds delivered similar investment exposure with worse outcomes than if one had simply taken the same amount of risk in the US stock market.

In earlier periods, hedge funds generated more benefit relative to stocks. For instance, from 1993 to 2003 the hedge fund index returned 11.1% per year when the risk-equivalent US equity return was 8.3%. Perhaps the amount of hedge fund assets has escalated much more quickly than the supply of investment “mistakes” to exploit.

Not “Absolute Return”

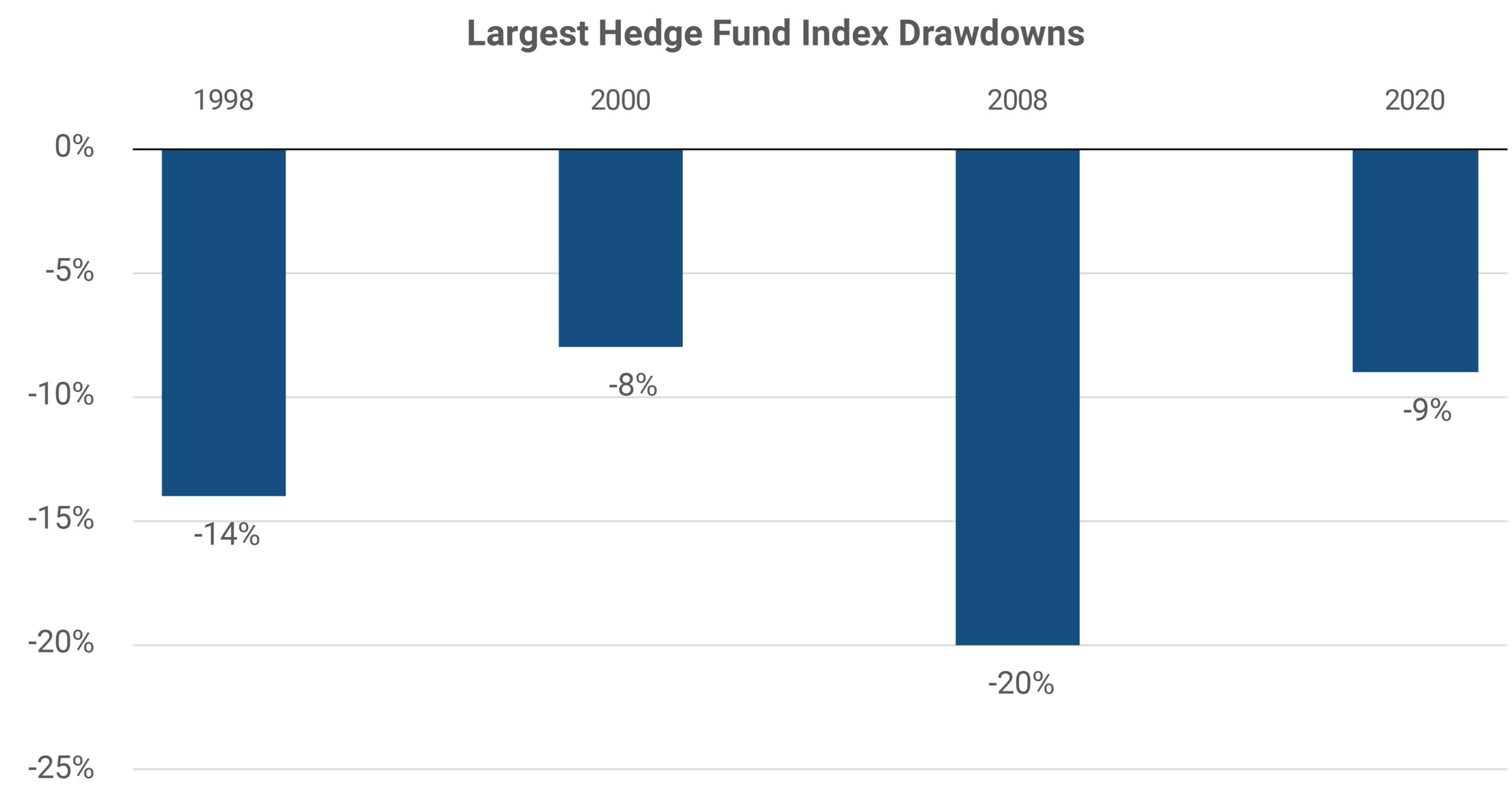

Another term used for the hedge fund category is “absolute return” implying a positive return in any investment environment. However, that is not the case. Because hedge funds have a high correlation to the stock market, they typically lose money at the same time that the stock market is suffering. The chart above shows the four largest drawdowns of the hedge fund index over the past 30 years. In each of these occasions there was also a selloff in the stock market. The 1998 drawdown included and was amplified by the spectacular collapse of the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management.

Enormous Fees

On average, hedge fund managers have skill. The problem is that more than all of the benefit of that skill ends up with the fund managers, leaving a losing proposition for the clients. As noted above, the hedge fund index return was 4.1% per year from 2010 through 2023. A typical hedge fund fee structure would be a management fee of 1.5% of assets under management and 15% of any performance over a threshold (which is often zero). A gross return of 6.6% would be needed to obtain a net return of 4.1% after the 1.5% management fee and a 1.0% performance fee. This means nearly 40% of the gross return (2.5% out of 6.6%) was taken by the fund managers, on average. The net effect of the fees is to leave the investor worse off than if the same amount of risk was taken in the stock market.

The fee structure provides incentives at both ends of the spectrum. For an up-and-coming hedge fund manager, the incentive is for higher risk. If the big risk pays off, the rewards are handsome. If the risky investments blow up, the manager closes up shop and starts a new fund. For a large established hedge fund, the incentive is for lower risk. For a $10 billion fund, a middle-of-the-pack 6.6% gross return is good enough to stay in business, and the 2.5%/year of fees generates $250 million a year – a nice source of contentment for the partners and employees. The investment strategy becomes more cautious to reduce the odds of a firm-threatening investment loss. Likely because of this incentive toward caution, the risk taken by hedge fund managers has fallen over time. The annualized investment risk of the hedge fund index was 8.4% from 1993 to 2003 and just 4.7% in the ten years through 2023. This choice by hedge fund managers to take lower risk has led to lower returns for hedge fund clients.

Not Transparent

Because hedge fund managers are not subject to the investor protections in the 40 Act, they have a wide degree of latitude regarding the information they share. Information about holdings is delivered with a lag and rarely provides a complete picture. Strategies, leverage, and risk can change meaningfully without notice to the client. Investors with significant holdings in hedge funds are at a disadvantage – the lack of knowledge about what the hedge fund managers are doing reduces the ability to understand and manage the entire portfolio.

Liquidity Risk

Investors in hedge funds who change their mind typically have to wait to get all their money back. It usually takes three months to a year between the decision to exit and the actual return of all investments. Moreover, the hedge fund manager can choose to delay or suspend redemptions altogether. During the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 – 2009, many hedge fund investors wanted to get out of poor performing or collapsing hedge funds and were unable to do so.

Tax Inefficient

Hedge funds are particularly poor choices for taxable investors. Because of the high turnover of investment positions at most hedge funds, the capital gains will tend to be short term in nature. For affluent investors, short-term capital gains are taxed at a high rate – up to 37% Federal and 13.3% for a California resident. An individual investor typically does not have visibility over the tax obligations being generated by their hedge fund investments. The final accurate numbers are delivered in K-1 reports late the following year – too late to know what the correct withholding tax payments for the prior year should have been.

Who Should Invest in Hedge Funds?

The investors who may benefit from investing in hedge funds are those with the resources to identify the better ones in advance. There is much more dispersion in outcomes from hedge funds than from active managers in liquid mainstream asset classes. According to a JP Morgan report, the performance of the top quartile of hedge funds over the past decade exceeded the performance of the median hedge fund manager by 7.5% per year or more[5]. An organization with skill at selecting “top quartile” managers in advance will be rewarded for the effort. Large, sophisticated institutional investors with experienced investment professionals such as the large university endowment funds have had the means to participate successfully as hedge fund investors. Such an investor will have direct access to the manager, visit the manager’s premises frequently, and spend as much as a year undertaking an in-depth analysis of the people, investment strategy, prior performance, and business operations of a hedge fund manager before making a choice to invest. If your hedge fund manager selection process is done with this exceptional level of diligence, you might have reason to participate. Otherwise, there is a good chance of ending up with an average hedge fund portfolio or worse, with all the drawbacks described in this paper.

Summary

David Swenson, the masterful Chief Investment Officer of the Yale University endowment, wrote a book of advice for individual investors called Unconventional Success[6]. The recurring message of the book is: “Don’t try this at home.” Individual investors have nothing like Yale’s experience, access or resources for screening hedge fund managers, and should not attempt to do so. Instead, the book argues, the emphasis should be on well-constructed portfolios of liquid asset classes at the lowest possible implementation cost. We support the arguments in the Swenson book wholeheartedly. As discussed in this paper, the average outcomes obtained by hedge fund investors have been disappointing for more than a decade, and individuals are more likely to succeed as investors if they avoid the category altogether.

[1] Source: BarclayHedge: https://www.barclayhedge.com/databases/global-databasee

[2] Source Bloomberg: Hedge fund return data in this paper uses the Credit Suisse Hedge Fund Index (HEDGNAV)

[3] Source Bloomberg: HEDGNAV, SPXT and USGG3M indices

[4] Hedge fund reporting is voluntarily, and funds that fail or have bad outcomes are less likely to report – “survivorship bias” is estimated to add at least 2%/year to index returns.

[5] Source: JP Morgan Guide to Alternatives 1Q 2024

[6] David Swenson, Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment, Free Press, 2005.

Disclaimer

The information and opinions contained in this presentation are for background purposes only and do not purport to be full or complete. No reliance may be placed for any purpose on the information or opinions contained herein. Atlas does not give any representation, warranty or undertaking, or accept any liability, as to the accuracy or the completeness of the information or opinions contained herein. This presentation does not constitute an offer or solicitation to any person in any jurisdiction. Any such offering will only be made in accordance with the terms and conditions set forth in a private placement memorandum or other offering document. Recipients should not rely on this material in making any future investment decision. We do not represent that the information contained herein is accurate or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice. Certain information contained herein (including any forward-looking statements and economic and market information) has been obtained from published sources and/or prepared by third parties and in certain cases has not been updated through the date hereof. While such sources are believed to be reliable, Atlas and its affiliates do not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Atlas does not undertake any obligation to update the information contained herein as of any future date. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole. Any illustrative models or investments presented in this document are based on a number of assumptions and are presented only for the limited purpose of providing a sample illustration. Any hypothetical performance information contained herein does not represent the results of actual trading using client assets but were achieved by means of the retroactive application of a model. Any sample illustration is inherently subject to significant business, economic and competitive uncertainties and contingencies, many of which are beyond Atlas’s control. One of the limitations of hypothetical performance results is that they are prepared with the benefit of hindsight. In addition, hypothetical trading does not involve financial risk, and no hypothetical trading record can completely account for the impact of financial risk in actual trading. For example, the ability to withstand losses or adhere to a particular trading program in spite of trading losses are material points which can also adversely affect actual trading results. There are numerous other factors related to the markets in general or to the implementation of any specific trading program which cannot be fully accounted for in the preparation of hypothetical performance results and all of which can adversely affect actual trading results. This document may include projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets, intentions or expectations. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investments are subject to risk, including the possible loss of principal. There is no guarantee that projected returns or risk assumptions will be realized or that an investment strategy will be successful. No representation, warranty or undertaking is made as to the reasonableness of the assumptions made herein or that all assumptions made herein have been stated. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this document, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated performance level(s), or be suitable for your portfolio. The information contained in this document is based on matters as they exist as of the date of preparation of such material and not as of the date of distribution or any future date and Atlas does not undertake any obligation to update the information contained herein as of any future date. This document does not constitute advice or a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to deal in any security or financial product. It is provided for background purposes only and on the understanding that the recipient has sufficient knowledge and experience to be able to understand and make its own evaluation of the information described herein, any risks associated therewith and any related legal, tax, accounting or other material considerations. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her/its specific portfolio or situation, it is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her/its choosing. Investment advisory and management services are provided by Atlas Capital Advisors, Inc. Atlas is registered as an investment advisor with the Securities and Exchange Commission.